Poverty, Place, and Power in Northumberland Park

We have an ambition to incorporate “data democracy” in place-based change, whereby communities shape the data and knowledge that will lead to improving their lives. We have been funded by Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) Insight Infrastructure to understand (particularly Black) communities’ perspectives on child poverty data.

This is our first blog in a series of four where we reflect on the community-based research process and our early findings and reflections.

Saga Woman was a satirical character from the Catherine Tate Show - a posh, pretentious upper-middle-class mother who reacted with exaggerated horror to everyday situations, particularly encounters with working-class people. In one episode, she 'takes a wrong turn' and ends up in Tottenham. Panic ensues. She instructs her children to 'remember the time we were on safari in the Serengeti - keep the windows and doors locked, and don't let the locals see the windscreen wipers moving in case they try to rip them off'. Over four million people watched this episode when it aired in 2006.

Some jokes work because they do interesting things in the relationship between the familiar and unfamiliar. In this case leaning on something familiar, a widely held perception of Tottenham as dangerous, chaotic, poverty stricken and Black, and in the context, something unfamiliar, a caricature of a white upper-middle class family. For me, this sketch stung. I grew up in Tottenham, in Northumberland Park, and recognised both the grain of truth and the fundamental misunderstanding in Catherine Tate's portrayal.

This tension between external perception and lived reality drives our current work on child poverty. Through our JRF Insight Infrastructure Convening project we are working with the people of Northumberland Park to explore child poverty and ethnic disparities, focusing on data interpretation through lived experience.

This is our first blog in a series of four where my colleagues and I reflect on the community-based research process and our early findings and reflections. Our work will culminate in a webinar in late autumn and you can stay in the loop by joining our learning community.

Our Approach

This project is a collaboration between Place Matters, Just Knowledge, Roots and Rigour and North London Partnership Consortium (NLPC). We are working together to explore how data can be used to empower and give agency to people rather than simply describe their circumstances. Or worse still, be used to other and disenfranchise.

We each share a commitment to doing research that centres the people most directly affected by the data, or issues under study. We recognise that our current conceptual resources are, by observation, inadequate for solving major social challenges like child poverty. While this kind of work goes by many names - Place Matters uses the term Data Democracy, others may call it community research or community-led research. As part of this approach, I am particularly drawn to the framing of Epistemic Justice. Whatever the label, the fundamental commitment is to walk in the direction our communities take us.

In this case, our community colleagues are the people of Northumberland Park, an estate in Tottenham where I grew up. Northumberland Park ward has the highest Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score in Haringey. At a household level, Northumberland Park was ranked eighth out of 7,264 Middle Super Output Areas in England and Wales for the percentage of households that were deprived across all four areas measured in the 2021 Census: Housing, Employment, Education, and Health and Disability. Working with the community, we will explore child poverty over four workshops, culminating in a report, webinar, and hopefully community action.

Following a methodology we developed with several partners on this project in previous work, we provide communities with bespoke, high-quality data analysis and visualisation that connects to their own interests and observations. Rather than presenting data as definitive truth, our approach starts from a simple recognition that any data can support an infinite number of interpretations. And, while we value theoretical and conceptual frameworks, we believe there are distinct epistemic advantages to interpretation rooted in lived experience of the issues the data claims to represent.

As with any research project involving people, we spent our first session simply getting to know participants and eliciting their initial responses to the concept of ‘child poverty’. To allow for unfiltered reactions, we deliberately did not display any data. The session was large, with 17 participants ranging from grandmothers to teenagers, held at the Neighbourhood Resource Centre in the heart of Northumberland Park, where NLPC is based. We purposely aimed for a big turnout to gauge community interest, spark intergenerational conversations, and lay the foundation for a group that might want to continue engaging in the research process.

What Is Child Poverty?

To help to structure people’s initial thoughts on Child Poverty we used the Grid Elaboration Method (Joffe & Elsey, 2014). The method is a simple way of eliciting reactions to a topic without initial input from the facilitator. In this case everyone was given a sheet of A4 with four boxes and simply asked to write or draw one thing that comes to mind when they think about child poverty in each box.

The results were fascinating. Concepts ranged from the psychological to the institutional and the structural, showing how complex the concept of child poverty is and also how, through lived experience, comprehensive understanding can emerge. For instance, one member of our group discussed how children are stigmatised for their poverty in school:

“Also from school, they get abused because […] they're not dressed well […] they don't look well.”

This stigmatisation was also seen as something that can persist over time:

“If you are in poverty and you're in this impoverished area, then you don't really matter, per se.”

“If you are in poverty and you're in this impoverished area, then you don't really matter, per se.”

“Your postcode, your family background, that will follow you”

Another emerging theme was the administrative burden (Herd & Moynihan, 2018) related to being poor and accessing relevant support and services such as employment, mental health or housing.

“When it comes to children in poverty, it's a waiting list. There's a long system of just waiting and [getting] no result, no like, no improvement or upgrade to their own needs and care”

“In addition to that point, that's if the parent has the know how to access support for them”

“Services that are good, they're out of the borough. So now people have to travel, and then that's where the dangers come in, because there's some young people they can't go to other post codes, or they can't travel that far because they can't afford the TFL”

The group, and in particular the young people, gave a scathing analysis of the broader contextual challenges that shape their outlook and prospects for social mobility:

“Our generation, we were born when there's been multiple recessions then the pandemic, then Brexit. Well, Brexit then a pandemic, and then now we have what's going on now. So our generation […] don't know the better half of it. We don't know.”

“So it's a bit hard to have, like aspiration, especially for those who are born in Tottenham, when we look to our parents, our parents are still in the same place. We look to our friends and their family, they're still in the same place. They've worked, and worked and worked. For others, how long? And yet, look at how they’re living, there's nothing to show for the work they’ve put in, to the country, to the system”

Participatory Map Making

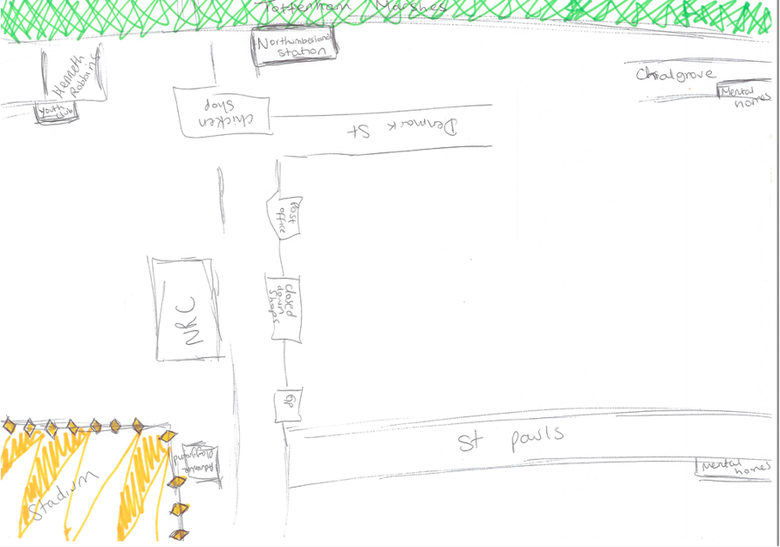

Following this discussion, we turned our attention to participatory map-making. There is a long history of dialogue between geography and psychology, going back at least to Milgram and Jodelet (1976), but our immediate aim was practical: to explore how people define their neighbourhoods, and to assess what spatial units might be appropriate for analysing data in later sessions[1]. Yet, when we invited participants to draw their local area, two things stood out.

First, in several cases, the “map of the area” consisted solely of the person’s own flat or a few blocks. This revealed how poverty may compress spatial perception, reducing the neighbourhood not to wards or boroughs, but to a few metres of lived space. This seems to challenge dominant conceptions of ‘place-based’ work, which often operates at the scale of towns, cities, or Local Authorities. These findings remind us that for some, “place” is profoundly, even unsettlingly, local.

Secondly, many maps prominently featured the Tottenham Hotspur stadium, which sits on the edge of my old estate, as a striking contrast to the surrounding poverty of Northumberland Park. In one particularly illustrative example, the map was drawn almost entirely in black pen, despite the availability of coloured materials, with two exceptions: the stadium and Tottenham Marshes. The stadium, rendered in gold, stands out as a gleaming symbol of affluence amid a largely monochrome landscape.

The illustrator described the area like this:

“Here on Park Lane, there's so many shops on both sides closed down. Like, I just feel like, because of the area being so, I won't say just broke, but it's obviously, once they open up, there's no customers. There's no clientele to even purchase the thing, so they don't stay open.”

“And then up here, all the way at the top of Park Lane, I’ve got the stadium, which is all gold and diamonds and money, money, money.”

The imagery captures a profound spatial and economic juxtaposition: the hyper-visibility of elite wealth set against the invisibility or decay of everyday urban life. As a social and cultural psychologist by training, even the representation of the Stadium as being at the ‘top’ is interesting and may indicate the ways in which social hierarchies become intertwined with our understanding of physical space.

In future sessions, we plan to explore whether this proximity between extreme capital investment, embodied by a Premier League stadium, and extreme local deprivation is unique to Northumberland Park or part of a wider pattern, illustrating the principle of our approach – providing data and analysis that meets the communities’ needs and interests. What is clear at this stage, is that for most people in our group the presence of the stadium implies or signifies a combination of neglect and contempt for the local community.

What next

We ended the session with a discussion about the impact, good and bad of having Tottenham Hotspur right outside. We are planning a range of analysis for our next session in a month’s time. Some people in our group clearly had more to say, and for some it seems that a one-to-one approach might be more appropriate.

From the perspective of a researcher, it feels like we have an amazing opportunity to learn, which I think is all we can ever ask for. Just as our session ended, the space in the community centre that we used opened as soup kitchen, many people gathered for food. Including young people.

My colleagues had been asking me how it might feel to return home, and my honest answer is I didn’t really feel anything until that soup kitchen opened and I realised that if not for a few friends, and particularly their mothers, I would have been using it had it been available at the time. There is survivors’ guilt there. But also, a recognition that although I don’t have the power to directly solve all the problems in the area, I have skills that I can put into the service of the community – and I am grateful to have the opportunity to serve and to contribute. As the great poet Yasiin Bey (aka Mos Def) put it “There’s grief here, there’s peace here, it’s easy and hard to be here”.